.

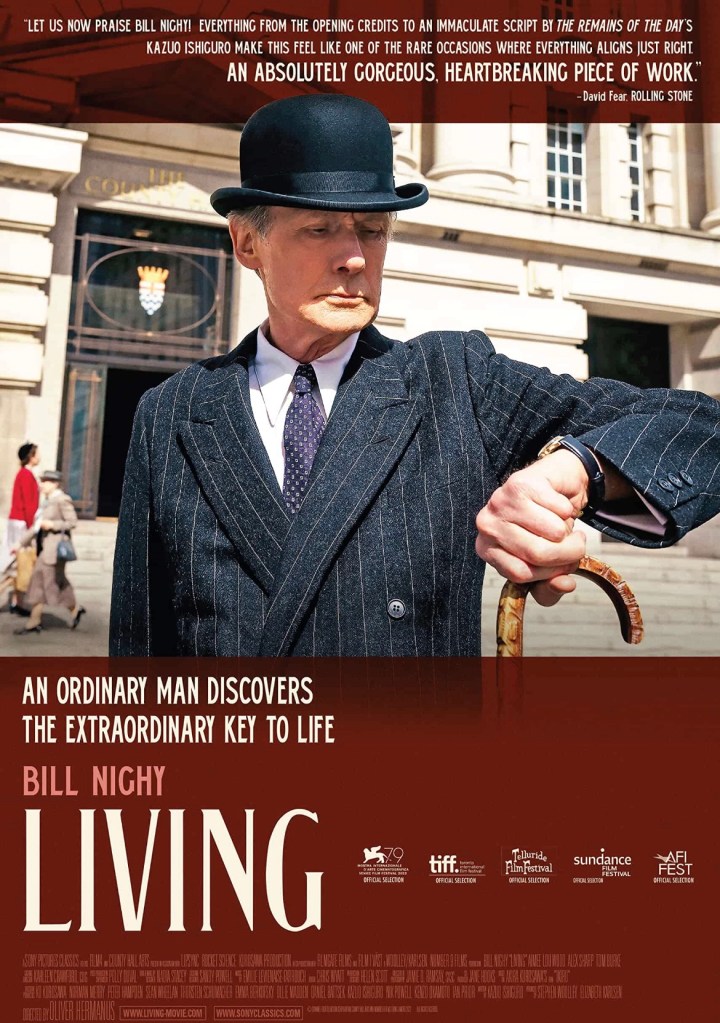

On the surface Living seems to be a very British film. A buttoned up, bowler hatted gentleman in early 1950s London discovers he is fatally ill and starts to re-examine his life and identity while the dutiful but largely repressed people around him have to adapt to the changes this brings in him. The setting is all steam trains, red double decker buses and tea rooms and it does feel very akin to movies of the time like Brief Encounter and The Titfield Thunderbolt.

What is interesting about this is that the source material is Japanese. Living is actually a very close adaptation of Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 movie Ikiru, which itself was inspired by a Russian novella; The Death of Ivan Ilyich by Tolstoy. Knowing this the comparisons between mid twentieth century UK and mid twentieth century Japan do quickly come to mind. Both societies had a focus on honour through responsibility, both shied away from public displays of emotion and both were quite heavily bureaucratic. These similarities in the national identity were no doubt at the forefront of the mind of British/Japanese writer Kazuo Ishiguro when he was writing the screenplay.

With all of its international pedigree though (the director Oliver Hermanus is from Cape Town) the heart of this story is bigger than this. It isn’t about being from Russia, East Asia, Europe, Africa or any single place in the world. Living, as the title suggests, is about human existence.

They do say that the one thing that truly connects all of us on this planet is that we will live and we will die and this film finds a way to handle both of these hand in hand. It’s not the first movie to tackle this but it does do it with real beauty and simple filmic poetry.

Bill Nighy has never been better, his performance is one of such subtly as to match Anthony Hopkins in another Ishiguro story, The Remains of the Day. Ishiguro’s novels, The Unconsoled, When We Were Orphans and Never Let Me Go included, have long had a focus on end of life retrospection, struggles for agency and the unspoken consequences of actions and his skill is in how he examines these themes lightly but with power. His works can leave his characters, and his readers, a little raw but he never puts people through the ringer. He brings all of this masterful storytelling approach to Living and watching it is a moving and cathartic experience. One again he has taken us on an emotional journey that is both out of reach and utterly tangible. It isn’t a hard watch at all though, the central conceit is sad but the film is actually lovely.

.

The Ripley Factor:

I’m some respects this is centred around a very male sense of being, certainly the expectations around the protagonist’s behaviour, his stoicism and reluctance to show sentiment are gender specific. Part of the emphasis of this is to surround him with similarly restrained men. The one key woman in the film though is the light that draws him out. He tries to find solace in the company of a man but to no avail, it is definitely a woman that eventually inspires his hope. This isn’t as clumsy as it sounds but she too demonstrates a certain type of gender trait, one it is made clear is not shared by all women, but is tied to femininity at some level and they way these characters play off each other is delightful. Aimee Lou Wood is wonderful in the part and matches Nighy at the height of his acting powers perfectly.